|

Bob Dance's artistic roots dig deep into Virginia soil and wind their way back to England. "When you trace the family name back, you start finding artists. You wonder sometimes if you weren't set up genetically for these kinds of things," he says. "For some reason, I always wanted to draw." Dance's earliest memories involve art: They began in Tokyo, where he was born. The art on the walls were prints by Japanese artists such as Utagawa Hiroshigi, Katsushika Hokusai and Kitagawa Utamaro. "The minute I saw them, I always wanted to do it. I wanted to make something appear as I saw it." Looming war with Japan pushed him and his American parents, Stuart and Dorothy Dance, back to Virginia in 1941.

They settled in Midlothian, where his father's people had farmed for generations, before the tobacco business took the Dance family to various locations where the leaf was king. What is a person to do when high school career aptitude tests score high for engineering, but painting, not machines and bridges, is in your blood? Figure out what your passion is and engineer your life to achieve it. It's a lesson for everyone in the same boat, regardless of age. Art won. Today Dance, at 67, is as a professional traditional realist artist whose alkyd and watercolor nautical paintings appear in numerous collections, galleries and exhibitions. Families headed down U.S. 70 toward Morehead City, N.C., probably have passed his studio. It's a 13-by-13 room over a woman's dress shop in Kinston, N.C., a tiny former tobacco town turned toward cotton and attractions such as King's BBQ, where tourists and townies take a meal break. Virginia, despite its genealogical hold, didn't anchor Dance. For years Dance lived in Winston-Salem, N.C., working first as an ad agency illustrator and then in his own free-lance commercial art business. As age 40 approached, though, he took an early midlife plunge into the fine arts. "I got tired of deadlines. Got burned out after awhile. I just wanted to paint what I wanted. When you're in an agency, or free-lancing, everybody's telling you what to do, so you don't feel you're doing what you can do best." He tested the waters, however, before he gave up his day job. His paintings had been selling, and he had developed the discipline needed to make a living at it. There are some essentials that make such career switches possible: education, experience, vision, discipline and perseverance. Dance had them all. This artist isn't a beads-and-ponytailed stereotype. "I don't look like an artist. I just look like an old guy who's just bald," he says. "The best artists I know are extremely disciplined people. The artists I've known who are not disciplined and who are blowing up all the time when someone criticizes their work don't learn. And they're not invited back." Making art, which is a business, doesn't depend on mood or whim. It requires regular office hours. So weekdays, Dance puts in a full day's work, dressed in khakis that invariably become spattered with paint. He's a demanding painter, producing only a dozen paintings a year - slow as cold molasses sliding down an inclined plate, he says. He'll put 20 or 30 glazes on his alkyd paintings to give them deep luminosity and perspective. The business term "continuous quality control" is a goal: "I've never been able to arrive completely satisfied," he explains. "There's always something wrong. I've never met a good artist who was satisfied with his work. I've met a lot of lousy artists who were perfectly satisfied with their work and thought that it was done by the hand of God. If I were happy with my work, I would be worried. You're not growing if you're satisfied." Tenacity and passion are requirements for self-employment, in the arts or anything else: "If you're not tunnel-visioned about what you want to do, you probably won't succeed. You have to stay focused and work hard. "I was lucky enough to succeed. If you're an artist and can put food on the table, you can consider yourself a success, I think." His mostly nautical paintings command $3,000 to $20,000, depending on size and medium.

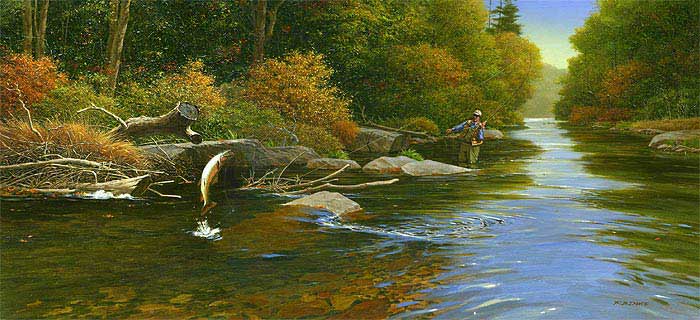

His watercolor prints, such as botanical prints of flowers and birds, sell for much less, and part of the profit goes to fight multiple sclerosis, which took his first wife. Dance is awed by nature - standing in rivers fly-fishing for trout, watching a fishing line arc across water, sailboats racing across lakes, the sky in all its manifestations - and "anything that flies: birds, butterflies or airplanes." After painting, fly-fishing is his outdoor lure.

"When you catch a fish, it's like pulling jewels out of the water. Most people release them; I do, too. They're so beautiful, particularly the brook trout, which is the only trout native to the Southeast. Some of the reds in them look like they're on fire." Dance doesn't miss a chance to revel in nature. "The one quality that artists have that other people may not is to be 'immature' enough to look at everything with a fresh eye. You don't see many mature people who are interested in the color of nature. Nature is always a surprise, always presenting new things, if you sit there and study it." He's a cloud-chaser.

"He's the kind of guy that might see a cloud formation on the way home from the grocery store and then follow it for the next four hours just to see what becomes of the shapes as they evolve," says Dance's son Scott, who owns a Los Angeles company - www.artwebsites.net - that specializes in getting artists on the Internet. He set up a site for his father: www.rbdance.com "Some people think my paintings are known for my clouds, although sometimes I don't put clouds in them," the artist says. "Clouds are full of color. Toward the end of the day when then sun's going down, they pick up all kinds of color, reflected light from the ground and from the sunset. It changes so quickly you can't stand there and paint it. About the only way to do it is to pursue the clouds, make photographs and use them in what you're painting." There are limits, however; and a main one is personal observation from the deck of an ocean sail boat in rough seas: "I've gotten seasick in ocean sailing, which is really embarrassing, because nautical art is my field. I don't like anchoring in the ocean and going up and down and sideways." For those paintings, he uses photos, model boats he builds, imagination and his three sons, since "posing for Dad was something all of us did," Scott Dance says. Modeling - as a fisherman in full gear on a model of a deck, for instance - was so routine "it was like being asked to take out the garbage." All that outdoor experience and the influence of Japanese artists and perhaps of his engineering aptitude surface in composition: "The simpler the composition, the stronger it is," he says. "Everything I look at, I look at with a sense of composition." Then the engineer in him speaks: "I'm always amazed at how form follows function in objects like airplanes. Ugly airplanes usually don't fly well, but beautiful airplanes and beautiful boats, beautiful mechanical systems usually work well." The Dance art genes have surfaced in the next generation: Mark as an artist in Chadds Ford, Pa.; Scott in Web-site design and writing in Los Angeles; and Stuart in sound design on Broadway in New York City. The senior Dance plans to continue painting with passion for the rest of his life. "As long as you have your health, vision and stamina, why not?" he asks.

|

||||||||||